ONLINE Exhibitions

Hidden Histories

October 2020

Narryna seems to epitomise the success of the early colonial free settlers. Its neo-Classical façade radiates an air of genteel respectability which is echoed by elegant interior furnishings. An atmosphere of domestic comfort, security and prosperity prevails. However, when one probes beneath the veneer, different histories emerge. Hidden Histories is a series of installation works that brings to light untold stories, focusing on the lives of women – both free settlers and convicts.

Hidden Histories is guest curated by Dr Llewellyn Negrin. Participating artists are Frances Watson, Janine Combes, Jane Slade, Julie Payne, Christl Berg, Irene Briant, Denise Rathbone, Chantale Delrue and Janelle Mendham.

In the 19th century, the home was identified with the woman as a result of the demarcation between the public and private spheres. Narryna’s interiors are a particularly apt location in which to explore these forgotten lives. This photo gallery shows a selection of works, visit Narryna to see the entire show.

Click on the recording below to listen to guest curator, Llewellyn Negrin discuss Hidden Histories.

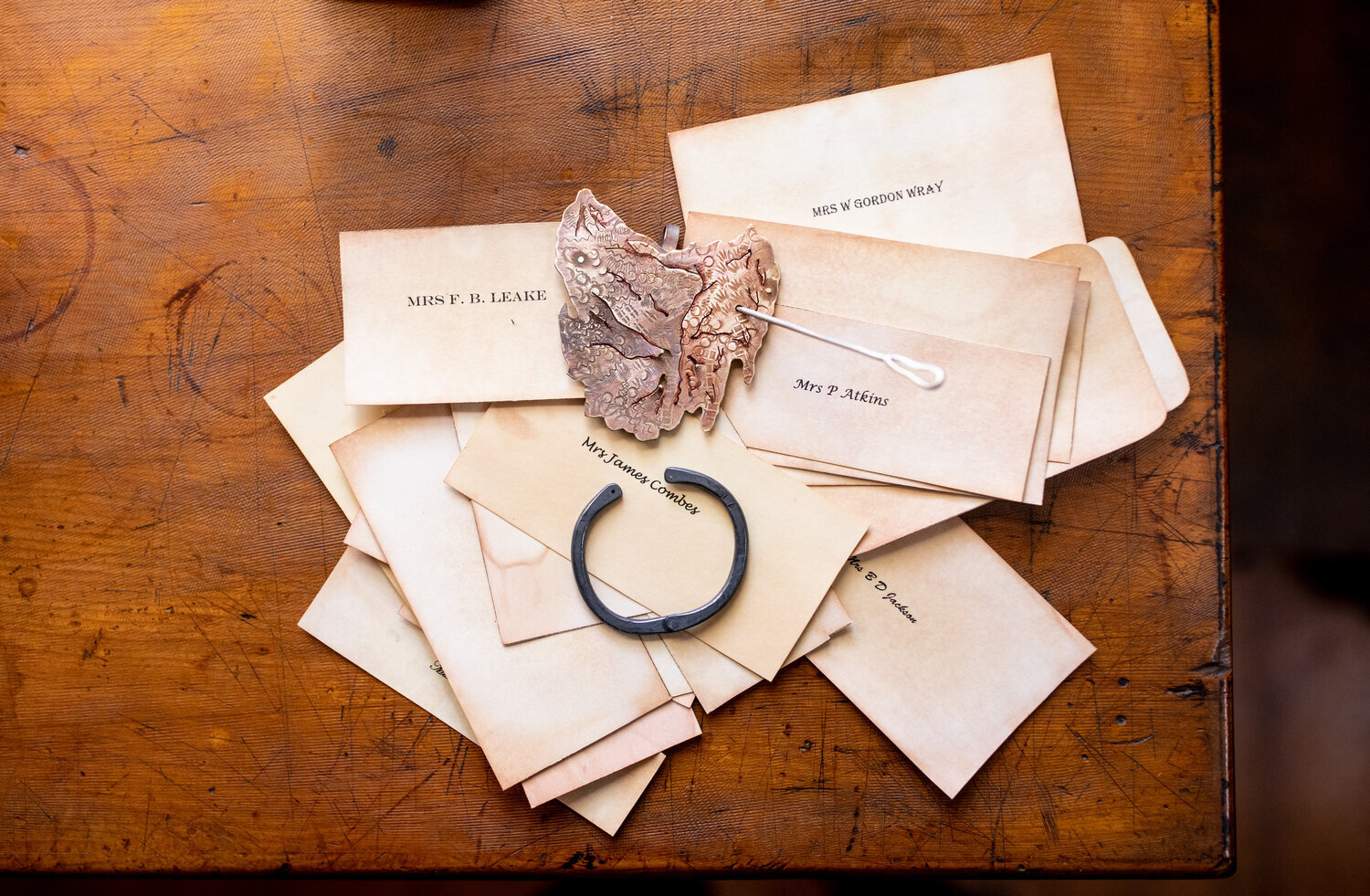

Janine Combes

Janine Combes’ series of works reflect on the constant pressure to maintain one’s reputation and the ever-present threat of ruin that may come through breaking the rules of social etiquette. Taking as her starting point everyday objects associated with 19th century women’s social interaction such as teacups, calling cards, letters and sewing needles, she endows them with a sinister edge. Thus, button hooks have an extra hook to catch the unwary while sewing needles are pushed through objects with force. Improper thoughts and words are concealed or burnt.

Janine Combes’ jeweller’s eye is also fascinated by items of dress and adornment such as the chatelaine (a set of short chains attached to a belt for carrying useful household items such as scissors and thimbles) and a skirt lifter (a device used to lift the skirts to keep them out of the dirt or to assist the woman to go upstairs).

Julie Payne

Secrets simmering below the surface emerge in Julie Payne’s text garden –The Whisper Garden– installed around the fountain. Beneath the outward sign of civility conveyed by the manicured lawns and ordered flower beds, there lurks another world of gossip and innuendo that threatens to disrupt the fragile semblance of decorum and equilibrium.

Chantale delrue

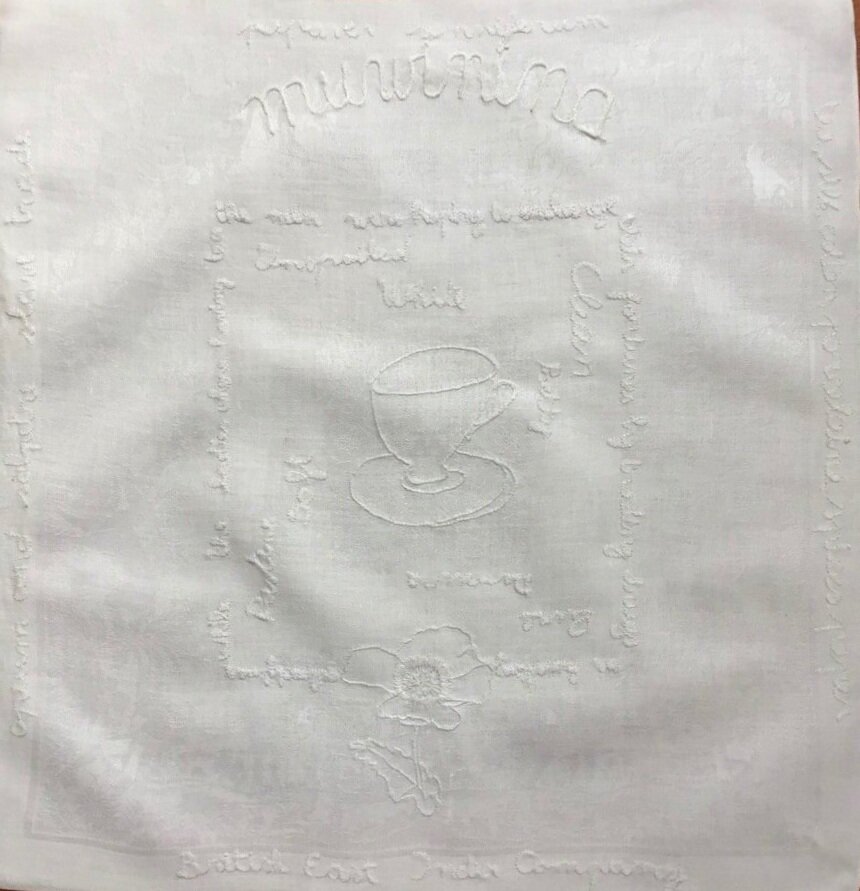

Witold Rybczynski, in his book Home: A Short History of an Idea identifies comfort, domesticity and elegance as the hallmarks of the 19th century bourgeois home which came to represent a sanctuary of moral and spiritual values amidst the cut-throat worlds of business and politics. An integral part of this process was the embroidering of household items and garments, a task to which middle-class women devoted many hours. Embroidery was regarded not only as a means of beautifying the home and of signalling the social status of its occupants, but as a token of the woman’s love and devotion for her husband and children. However, at the same time, it also speaks of another history – a history of blighted lives, frustrations and unfulfilled dreams.

Chantale Delrue’s series of embroidered items includes a pillowcase, a gentleman’s shirt, a napkin, hand towels and handkerchief. This pillowcase speaks of the consequences of spilling of seed in the colonial bed.

frances watson

While we appreciate that convict women were deprived of liberty, Frances Watson’s works speak of the restricted lives of colonial middle-class women as well as inviting us to reflect on more recent repression and displacement. Behind the construction of the home as a ‘haven in a heartless world’ there lies another reality of unfulfilled ambitions, hidden suffering, anxieties, and longings. The 19th century drawing room provided a gilded cage, a beautiful setting for the women of the family to perform musically and show off their feminine accomplishments to potential suitors. Possibly alluding to the cage crinoline which was the height of fashion in the 1850s, Frances Watson reflects on how aesthetic perfection underpinned prescribed lives.

In the dining room – the male domain – stands The Price of Passage. The cage holds a globe, a replica 19th century sailing ship (of the type captained by Captain Haig) and beneath the ship, red plastic fragments representing bloodshed in the worldwide program of colonisation. Atop the cage sits a crown and a bible – both motivators of colonisation. Beneath the globe lie bleached bones, shells and wood representing the price paid by the passage of so-called civilisation.

irene briant

Irene Briant’s work Trace reflects on the intimate engineering and hours of labour required in producing domestic textiles such as the knitted counterpane on Narryna’s huon pine bed

janine combes & chantale delrue

Janine Combes, Chatelaine for nine convict women, suitcase holding a series of notes in medicine bottles, suspended by chains from handcuffs with Chantale Delrue’s accompanying sound piece Narryna Gossip with the voices of imaginary English, Scottish and Irish servants.

Thank you to those who contributed to Narryna gossip: Jean Henley, Frances Watson, Elaine Mead, Maria Flynn, Ann Smith Thomson, Diana Cameron, Shola Flight.

christl berg

Christl Berg’s screen work, Anna, aged 9 years, 2019, juxtaposes an image of play – a girl jumping on a trampoline – with the inculcated Protestant work ethic evident in the samplers surrounding the monitor. These samplers were made by seven and eight year old girls as evidence of their proficiency in their stitches, letters and numbers and the Christian catechism. Childhood was denied for a life of care for a household’s linen, while at the same time, the fiction was maintained that women, as middle-class wives, mothers, daughters or maiden aunts, had sufficient wealth not to work.

with girls there is …, concertina book illustrating the types of activities that took place in Narryna’s nursery.

denise rathbone

Denise Rathbone pays homage to the resilience of the female convict servants who were employed in the household and expected to carry out their tasks seamlessly and out of sight, lest they be punished by being sent back to the Cascades Female Factory. Remember consists of thirty buckets, installed on the servants stairs and spilling into the outside courtyard. Each bears the name of a female convict known to have been assigned to Captain and Mrs Haig.

Remember installation, thirty galvanised buckets, decal, glass, geraniums, Narryna courtyard

jane slade

Jane Slade’s work, comprising of a series of wax impregnated undergarments of 19th century women, made by women for women, speaks of silenced desires, a longing for elsewhere and the shattering of broken dreams. Like the bee, each woman had their clearly defined role, convict-servant or mistress-homemaker, whether hidden in the shadows or as part of the decor along with the material possessions of the household.

Longing for Elsewhere (Waxen Forms)

The cloth of intimate apparel is dipped into hot beeswax then twisted, knotted, folded and hung as ghostly waxen forms. The cloth oozes with the sweet pungent smell of honey. In the heat of summer, the forms remain pliable and translucent while during winter the cloth becomes rigid, hazy and brittle. The shadows emitted by the sculptures change with the light, as do the stories of women from our past.

Shattered Dreams (Glass dome)

As part of the decorative interior, exotic insects, birds and animals were manipulated into shapes and enclosed in glass domes, cabinets and frames. Instead, the Victorian dome pictured here has been filled with discarded shards of text and miniature paper sculptures to reference a longing for elsewhere and the hidden histories of the women of Narryna.

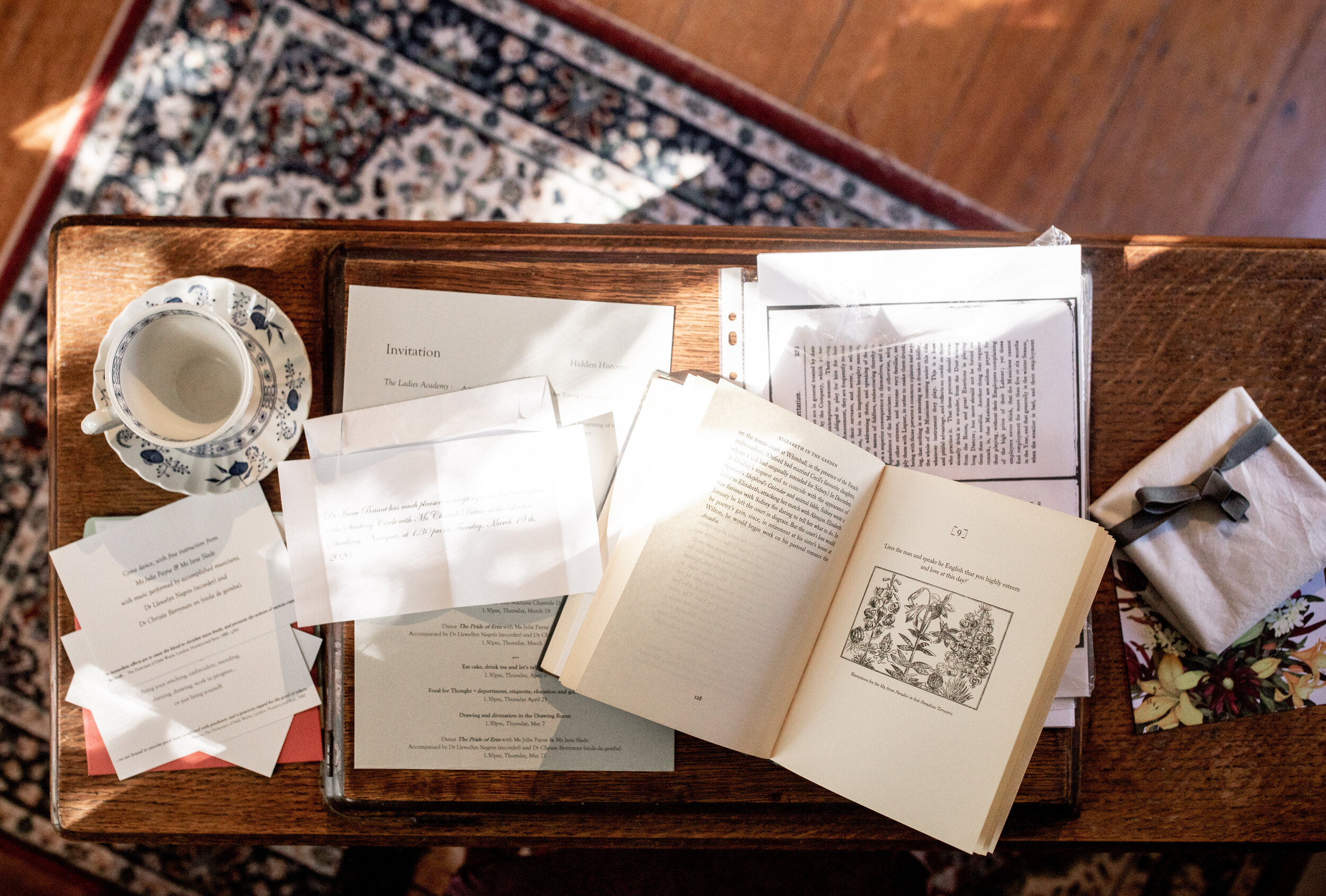

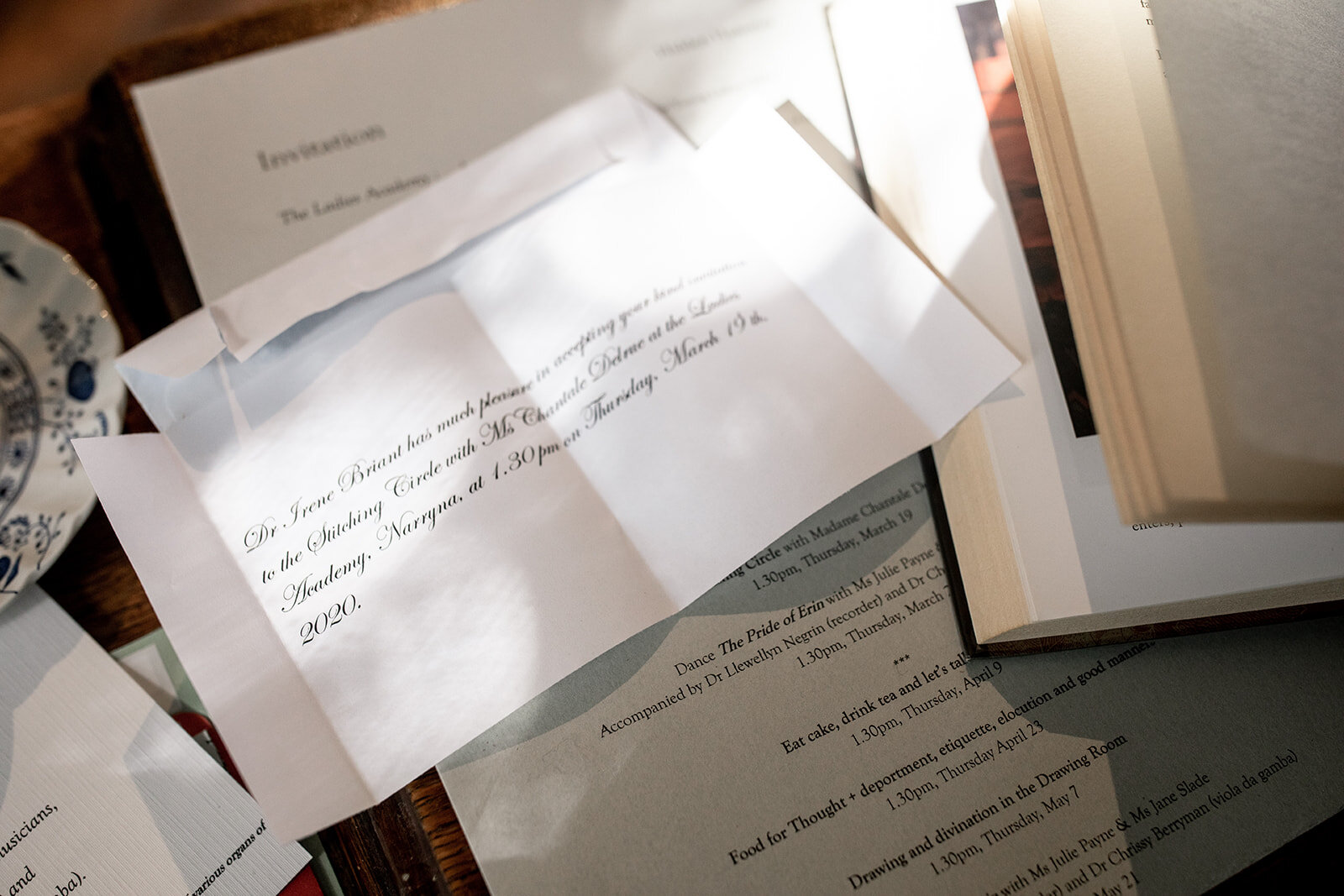

Janelle Mendham

With her husband, Captain Andrew Haig, on the verge of bankruptcy, Elizabeth Haig advertised an ‘establishment for the tuition of young ladies’ at the newly completed Narryna in a bid to make ends meet. Janelle Mendham’s performance work, The Ladies Academy re-enacts some of the activities that may have formed Mrs Haig’s original curriculum such as drawing, sewing and dancing. But the participants subtly subvert the bounds of propriety, taking command of the exhibition space as their own rather than withdrawing into the drawing room which was the area traditionally designated for ladies at the time.